BETWEEN LINES

Cospeculation, Design Fiction & Designer Agency

Between Lines is a critical, speculative design project that envisions uses of location data through four, near-future, design fiction films, a publication, and an installation.

This is a condensed case-study of my Master of Design Thesis completed during my two-years at the University of Washington.

This project is a critical investigation into how potentially harmful surveillant technologies are rationalized by technologists, produced, and deployed.

Simultaneously it explores how designers can rapidly prototype future technologies and showcase their potential impacts.

Combining my background in short film production and interaction design, I landed on an approach that combines traditional forms of speculative design, with cospeculation and design fiction.

I was responsible for the project definition, scope, planning, approach, implementation, and execution of all research and design responses throughout the project.

Project

Masters Thesis

Skills

Problem Definition, Research Planning, UX & Interface Design, Film Production

My Role

Designer, Researcher, Filmmaker, Artist

Timeline

3 Quarter's (Fall 2023–Summer 2024)

Collaborators

James Pierce, Burke Smithers, Laura Le

FIGMA — DAVINCI RESOLVE — FUSION — WEBFLOW

Project Update

Between Lines was accepted at the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’25), April 26–May 01, 2025, Yokohama, Japan.

You can read the paper here: Exploring the use of Speculative Concept Films for Co-Speculation around Data Ethics. DOI:10.1145/3706598.3713245

PROBLEM

systems, agency, and design

There is an increasing number of highly complex, technologically advanced systems being used behind the scenes of our digital world. Things like apps, websites, and the cloud infrastructure that powers them are becoming more complex with each passing day. There are many positive and negative tradeoffs. Often, the positives are widely marketed and shared with the public, while the negatives are swept under the rug unless there is a public outcry or ridicule about the technology.

Designers and design researchers currently lack a clear way to visualize and communicate the impact of these systems to the general public in a compelling way.

Approach

speculative design filmmaking

In this project, I focused on the consequences of location-based technology that are often overlooked in typical design and development contexts and on the potential for film to showcase potential futures in a compelling manner.

I created four short critical design fiction films in collaboration with my thesis chair, James Pierce. These films speculated about near-future interactions people could have with location-based recommendation systems in their everyday apps (things like GPS, shopping, insurance, and even jogging apps). I used these films to conduct 11 interviews with domain experts where we looked at the risks and ethics of the technology.

Approach

creating a composition of critiques

In creating film scenarios, I decided on a method requiring a strong conceptual composition of critiques. Knowing I would produce multiple films, James and I decided they should work together. Each film would address distinct critical themes—such as gentrification and corporate-state security collaborations in what became Avoidable Inconveniences.

While still discussing common overarching critiques, such as paternalism, surveillance capitalism, and reductions in agency. To achieve a diverse array of films, a significant part of the project early on involved generating broad high-level critiques. Details of the plot, specific scenes, and the intricate workings of the technology were not emphasized. Our films were shaped by three permeable categories: Surveillance Capitalism, Agency, and Technological Mediation. Each film was inspired by current events, themes in fictional films, and research reports. For instance, December 26, 4:36 pm, heavily draws on HCI research addressing emotional sensitivity and recommender systems. Key texts included “The Relevance of Algorithms”, “The Filter Bubble”, and “The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.”

Once I had the framework (critiques I wanted to address, the possible implications of the technologies, and what technologies they are similar to) we developed the details of the films. We created twenty scenarios, each with a one to two-sentence description of the scenario, setting, and character that specified the critiques and trends they addressed. All 20 scenarios were critiqued by designers, fellow researchers, and a subject matter expert. Our colleagues and experts noted that some scenarios offered "richer" sources of tension or addressed key concerns in their research, guiding us in selecting which concepts to develop further. In deciding which scenarios to cut, we balanced the subject matter, the manifestation of location-based recommenders, and the critiques involved. The final four scenarios were Avoidable Inconveniences, December 26th, 4:36 pm, Evidence of Insurability, and Routine Repetitions.

Deployment

speculative worlds in front of real eyes.

I conducted eleven interviews with four professional developers, one professional designer, three PhD students, one professional artist whose previous work focused on surveillance, one community activist engaged in philanthropy and nonprofits, and one assistant city attorney dealing with public data, culminating in a total of eleven interviews. Our participants’ domain knowledge and expertise allowed us to utilize participants in two roles: evaluators of feasibility and plausibility and collaborators in the act of speculating, critiquing, and understanding possible futures.

Each interview was structured the same—we would start with a brief introduction describing the project's critical nature and informing participants of any key definitions they might not know (often simply a brief explanation of speculative and critical design, then give a two sentence overview of the plot and the themes of the film, then play the film. Once the film had finished, we would wait for initial participant reactions or prompt them for their first thoughts, then work with questions from our discussion guide. We would spend roughly 20 minutes discussing the film, then move on to the next one. Once all films were viewed, we would then ask our closing questions, asking participants to reflect across all of the videos. The interviews would last between 120 to 180 minutes.

Outcomes

IRL.

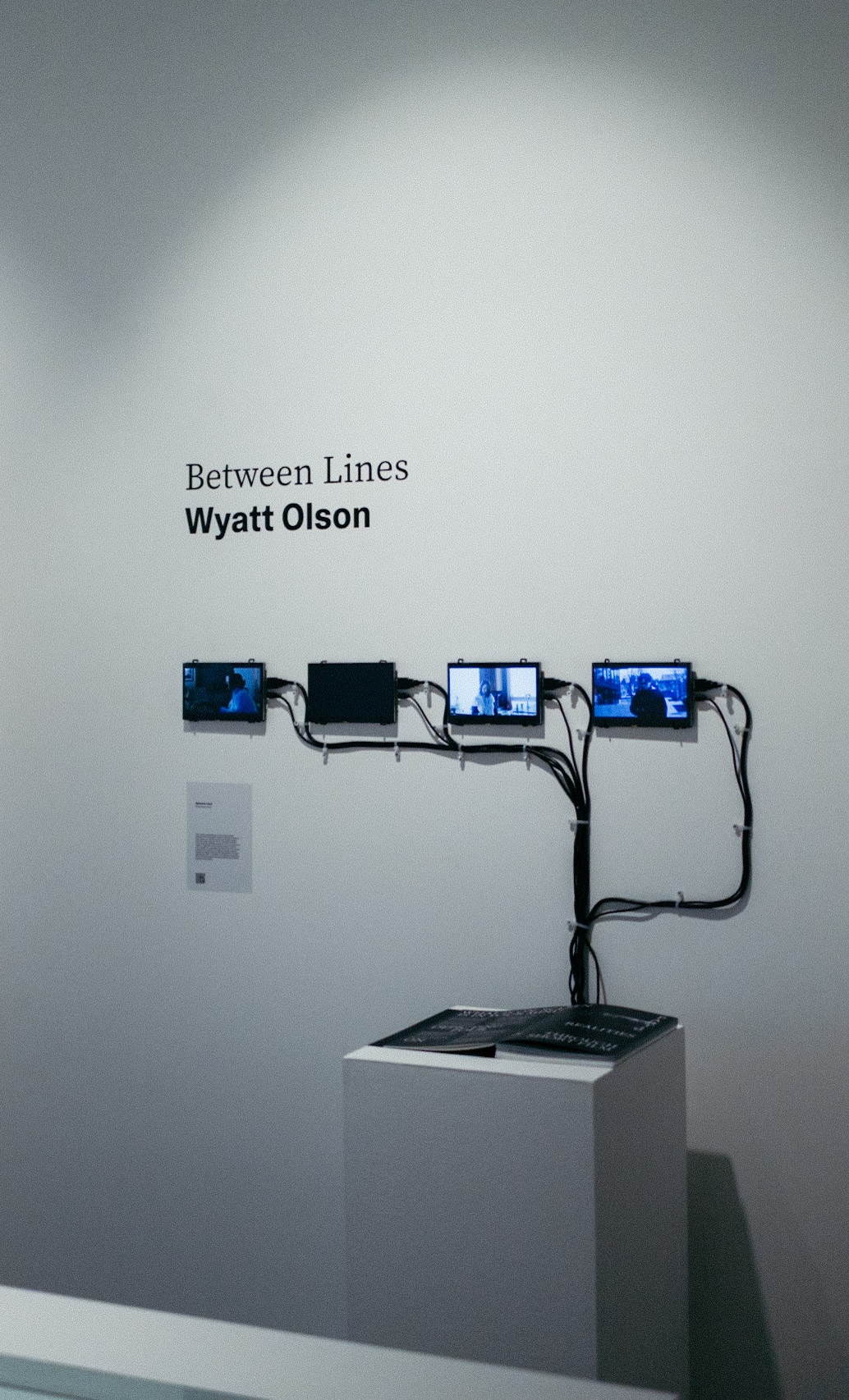

After the study was complete, I transitioned to analysis. I coded the transcripts, developing themes, findings, and insights. In parallel, I worked to create my final thesis publication and installation at the University of Washington’s Jacob Lawrence Gallery. The thesis was accepted for publication in the Association for Computing Machinery’s 2025 Computer Human Interaction Conference (CHI). You can access the full CHI paper via the ACM’s open access policy here: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3706598.3713245

Installation

In Real Spaces

Documentation of my work as part of the M.Des installation at the UW's Jacob Lawarence Gallery

Interaction Design

Wyatt Olson

Visual Design

Wyatt Olson

Burke Smithers

Filmmaking

Wyatt Olson

Laura Le

Rachael Winkler

Anne Winkler

Mary Olson

Nelly Quezada

Teresa McDade

Kenneth Nguyen

AK McDade

Mark Olson

Publication Design

Wyatt Olson

Installation Design

Wyatt Olson

Fabrication

Wyatt Olson

Laura Le

Mark Olson

Speculative Design Filmmaking

POSTMORTEM

How can _ designers _ rapidly prototype the future?

The future is unstable. Most disciplines spend vast amounts of time and money trying to best position themselves to capitalize on the most likely outcome of future outcomes, events, trends, possibilities.

Yet, who precisely brings that future into view? Designers are often tasked with realizing a specific vision of the future (their vision or, quite frequently, their organization leaders'). Creating a range of artifacts, including, mock-ups, prototypes, systems. Once released into the wild, these artifacts often permanently change society (see the AIGA's writing on ontological design).

Considering these ideas, we asked: How can we use design to anticipate concerning and contentious futures with these systems?

In particular, we wanted to focus on the consequences of technology that may be overlooked within typical design and development contexts. Methodologically, we also wanted to investigate how we can use the engaging and immersive format of film to project future scenarios that extrapolate current trends and do so in ways that elicit meaningful and generative discussions.

In this project, I created four, short critical design fiction films in collaboration with my thesis chair, James Pierce, speculating about near-future interactions people might have with location-based recommender systems embedded in everyday apps (GPS, shopping, insurance, and jogging apps). I used these films to conduct 11 in-depth interviews with domain experts, using the films as design probes, to understand how experts think and conceptualize the systems, risks, and ethics of agency, control, and manipulation.

How do designers think about the future?

Design teams, large and small, often make countless small decisions while creating a product or service. While some firms have adopted participatory approaches, methods for collaborative futuring remain few and far between. With this project, I simultaneously wanted to expand and iterate on existing methods of critical design speculation (leveraging my background in film production) to question an increasingly relevant and pressing topic: location data usage in recommender systems.

How We Think About Location Data

While location data may seem like a niche topic, designers often draw on the power of location-based recommender systems without knowing it. Location data has become embedded in contextual recommendations, customized profiles, search queries, advertisements, and social media.

At their most basic level, location-based recommendation systems are recommender systems that incorporate location information from a mobile device into algorithms to provide users with more relevant recommendations. These are increasingly complex recommendation systems behind the stable interfaces of the Google and Apple Maps, Uber and Lyft apps.

These systems are dynamic, often morphing, considering current and past locations, browsing, and purchasing activity across the web to inform increasingly contextual recommendations — and navigating our bodies through space to get there. This data has been put to use, for a variety of purposes, ocasionally veering into the dystopican:

ICE to pursue privacy approvals related to controversial location data

Automakers Are Sharing Consumers’ Driving Behavior With Insurance Companies

FCC fines AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile, and Verizon nearly $200 million for sharing access to users’ location data.

Many critical scholars argue that location privacy is a critical component of autonomy from state-sponsored and commercial surveillance systems. Yet, these systems are often hidden away, along with the data they collect.

Detailed Scenario Development.

Countless questions arose about how to develop the films. In creating scenarios, we decided on a method requiring a strong conceptual composition of critiques. Knowing we would produce multiple films, the team decided they should work together in concert. Each film would address distinct, scenario-specific critical themes without overlap—such as gentrification and corporate-state collaborations in what became Avoidable Inconveniences.

The films were also designed to share common overarching critiques, such as paternalism, surveillance capitalism, and reductions in agency. To achieve a diverse array of films meeting both criteria—distinct scenarios with shared themes—a significant part of the project early on involved internal debates and generating broader, high-level critiques. Details of the plot, specific scenes, and the intricate workings of the technology were not emphasized. Our films were shaped by three permeable categories: Surveillance Capitalism, Agency, and Technological Mediation, inspired by current events, themes in fictional films, and research reports. We drew on prior work and current events to inform the films' design and grounded them with subtle references to key events. For instance, December 26, 4:36 pm, heavily draws on HCI research addressing emotional sensitivity and recommender systems. Key texts included The Relevance of Algorithms, The Filter Bubble, and The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

With the established conceptual framework—focused on critique, possible implications, and related technologies—we developed detailed scenarios. We initially created twenty scenarios, each with a logline (a one to two-sentence description of the scenario, setting, and characters) specifying the critiques and trends they addressed. We included a three-frame storyboard for each scenario, using ShotDeck to pull visually and thematically relevant stills from existing films. This approach helped us align the concept, form of communication, and visual tone, combining mood and storyboards to flesh out each idea. These scenarios were then critiqued by designers, fellow researchers, and a subject matter expert. This feedback was crucial in narrowing down the final four scenarios that would be adapted into short films. Our colleagues and experts noted that some scenarios offered "richer" sources of tension or addressed key concerns in their research, guiding us in selecting which concepts to develop further. Scenarios lacking clarity, focus, or critical components were cut. In the downselection process, we balanced the subject matter, the manifestation of location-based recommenders, and the critiques involved. The final four scenarios were Avoidable Inconveniences, December 26th, 4:36 pm, Evidence of Insurability, and Routine Repetitions.

Making the Films

Once the scenarios were locked in, I moved on to the pre-production phase. Due to the project's condensed timeline and the number of films I aimed to create, I began a rolling production schedule. For each of the four films, I would write a script on Monday, create a storyboard on Tuesday, and send it to my talent on Wednesday. I would assemble a skeleton crew, including a gaffer, onset sound, and myself (camera operating and directing). Each week (often Thursday and Friday), I would assemble a rough cut of what had been shot the week before, doing a rapid color grade and making other minor adjustments. Occasionally, if I were not able to find help, I would record motion without sound (MOS) adding all audio in post-production. While I sacrificed greatly on lighting quality, camera stabilization, and a layer of refinement that might otherwise have been there, this approach allowed me to be incredibly flexible (shooting alternate versions, coming up with shots on the fly, etc.) in a more documentary style.

Once the films were edited (often a fast one to two-day process), I began to approach screen replacements. Artistically, I was opposed to text overlays on screen. While they provide greater flexibility, I prefer the naturalism and realism of showing UI on-device. This was debated heavily throughout due to the time on-screen text and UI graphics would save. However, I decided that the extra effort would pay off, not breaking the illusion of an alternate reality. To this end, each screen was replaced using Davinci Resolve’s built-in Fusion compositing tools. While I was initially able to replace all of the phone screens, due to some of them looking poorly (often due to difficult tracks and complex rotoscoping work), I pivoted to taking the interface I’d created for the screen replacements and using them in a series of reshoots. In the end, 50% of the interfaces were replaced in post production as originally intended, and 50% were reshot with stand-in actors.

Pre-Piloting and Piloting

After completing the initial versions of the films, I conducted a preliminary screening with two colleagues who specialize in data and privacy. This was less a traditional pilot and more akin to a test screening aimed at evaluating the clarity of the narrative, the critique being applied, and the depiction of algorithms within each film. The feedback was critical: the narratives lacked clarity, leading to misinterpretations of the plots; the role of recommendation systems was obscured; and the interfaces failed to effectively convey their intended messages.

In response, I revised each film, focusing on strengthening the narratives through strategic edits—including shortening the duration—to enhance narrative clarity. I also reshot and updated the user interfaces, ensuring each was of higher fidelity and more effectively communicated within the story's context.

Upon completing these revisions, I conducted another pilot with a subject matter expert in location data, privacy, and security. The revised films elicited fewer questions about the narratives and the roles of recommendation systems in the story. Instead, they sparked visceral reactions, indicating a high level of engagement with the themes presented. This feedback was encouraging as I proceeded to engage with my main study participants.

Participants + Recruiting + Study Design

Given the nature of the project and the constraints of a small team and condensed timeline, we took a pragmatic approach to recruiting, targeting two key participant groups: tech industry professionals and HCI researchers. Our focus was on recruiting 'experts,' defined as individuals with technical knowledge of recommender systems and an understanding of how and why these systems are developed. We were particularly interested in participants with insights into internal team dynamics and the defense of design decisions, aligning with our goal to explore perceptions of personal agency within these environments. Due to the project's condensed nature, we turned to peer schools within the university, reaching out to people with whom we had no prior relationships. Four participants were recruited via word of mouth; the remaining four were referred via snowball sampling.

Our participant pool consisted of four professional developers, one professional designer, one PhD student studying recommender systems, one PhD student studying surveillance, one PhD student studying predictive policing, one professional artist whose previous work focused on surveillance, one community activist engaged in philanthropy and nonprofits, and one assistant city attorney dealing with public data, culminating in a total of eleven interviews. Our participant's domain knowledge and expertise allowed us to utilize participants in two roles: evaluators of feasibility and plausibility and collaborators in the act of speculating, critiquing, and understanding possible futures.

Our study protocol consisted of a brief introduction describing the project's critical nature and informing participants of any key definitions they might not know (often simply a brief explanation of speculative and critical design). We would then begin with the films. Each film would be introduced with two pieces of information: a one-sentence plot overview and a one-sentence description of topics. We would then play the film. Once the film had finished, we would wait for initial participant reactions or prompt them for their first thoughts, then work with questions from our discussion guide. We would spend roughly 20 minutes on each film. We would then ask our closing questions, asking participants to reflect across all of the videos. The interviews would last between 120 to 180 minutes. The films would always be shown in the order seen in.

The study protocol was updated twice throughout the study. These times were after the second and fourth interviews. Our first iteration added additional questions, targeting areas of discussion we felt the team had overlooked. The second iteration of the study included adding two new components. The first item was a scenario summarizing the plot of the first film that would be read to the participant before viewing. The second item was a short animated video from a car insurer describing their RightTrack program (a similar concept to the service in Evidence of Insurability).

Once the interviews were completed, the recordings were transcribed using Dovetails' transcription feature. I conducted each round of analysis. While reading the transcripts, they inductively used thematic coding to identify thematic groups in participant responses. We formalized our approach to process and our findings in our CHI 2025 paper, Exploring the Use of Speculative Concept Films For Data Ethics.